|

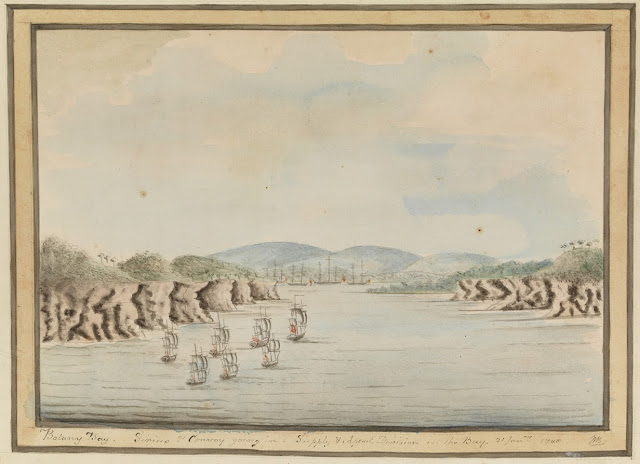

| `Botany Bay. Sirius & Convoy going in : Supply & Agents Division in the Bay. 21 Janry 1788' William Bradley |

"BLACK CAESAR," FIRST OF THE BUSHRANGERS

by J. H. M. Abbott

John Henry (Macartney) Abbott (1874 – 1953) was an Australian novelist and poet who was born in Haydonton, Murrurundi, New South Wales in 1874. He was the eldest son of son of (Sir) Joseph Palmer Abbott and his first wife Matilda Elizabeth, née Macartney. He was educated at The King's School, Parramatta and then attended classes at the University of Sydney before returning to the family property to work as a jackaroo. He published his first verse in The Bulletin in 1897.

In January 1900 he left Australia for the Boer War where he served as a corporal in the 1st Australian Horse, and later as a second lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery, but was invalided back to Australia in October 1900. He utilised his experiences in the war to write Tommy Cornstalk (1902), the success of which convinced him to move to London to work as a journalist. He returned to Australia in 1909 and worked for the next 40 years as a writer of novels, poetry and prose pieces for various newspapers and periodicals.

Originally published in the:

Truth (Sydney)

Sunday 28 October 1934

THE story of Australian bushranging divides itself naturally into three periods — that of the runaway convicts whom the terrors of the "System" drove to seek escape from its cruelties in the bush; that which had its beginnings about the time of the gold discoveries, when the bushrangers were generally free men of an adventurous and lawless type who were tempted into crime by rich and poorly protected convoys of gold; and that which was concerned almost entirely with the exploits of Ned Kelly and his companions.

The earliest bushrangers were prisoners of the Crown who had escaped from assigned service, or from the iron-gangs employed in road making and other public works, and had taken to the bush in order to avoid recapture.

THERE was little in the forest clad wilds upon which they might support life, so they were compelled to resort to robbery as their only means of existence.

In his report to the House of Commons in 1822, Mr. Commissioner Bigge, sent out to inquire into the public affairs of New South Wales, defined bushranging as "absconding in the woods, and living upon plunder and the robbery of orchards," and that may still stand as a fairly apt description of the pioneers of the profession.

Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), being the gaol of twice convicted and extra-refractory convicts, produced the earliest and most violent bushrangers, but they had at least one forerunner in New South Wales — the subject of this article — who made a name for himself in the very beginning of white settlement on Port Jackson, during the administration of the first Governor of the Territory, Captain Arthur Phillip, R.N.

It was not, however, until about the eighteen-twenties that bushranging on the mainland assumed anything like the proportions it had reached in the southern island in the first years of the nineteenth century. There it had its beginnings almost at the very start of settlement, and it was close upon half a century before the country ceased to be terrorised by more or less bloodthirsty gangs of freebooters, the scourge alike of settlers and aborigines.

The earlier bushrangers in New South Wales were rather loafers and "lead-swingers" than confirmed criminals. They usually sought a chance of slipping into the scrub whenever the vigilance of the sentries guarding them might be relaxed, and the wild nature of the country made it easy for them to get away.

It seems almost unbelievable, but is nevertheless true, that large numbers of them fled into the Blue Mountains, or along the coastal strip northward, with a hope of reaching the Dutch East Indies, India, or China. Very few of them could read or write, and had only the most fantastic ideas relating to geography.

It has never been even vaguely computed how many of them perished in the mountain gorges or the coastal scrubs in making these desperate bids for liberty, but the number must have been very great.

The majority of them, however, only hoped to live free lives in the bush. A few joined the blacks and remained with them for years, whilst others merely wandered aimlessly about until hunger hunted them back to inevitable punishment and renewed penal slavery.

Many remained at large until recaptured, subsisting by robbing settlers. When a man became "fed up" with bushranging, he gave himself up and was flogged.

A second offence entailed twelve months in an iron-gang. Subsequent abscondings involved transportation, if re-taken, to the Coal River (Newcastle) or to Van Diemen's Land.

And now we may turn to our first bushranger, and be edified to find that he bore one of the most famous names in all history — that of Caesar.

John Caesar was a powerfully built West Indian Negro, who had come to the Colony in the First Fleet, on March 14, 1785, he had been convicted at 'Maidstone and Sentenced to Seven Years' Penal Servitude and Transportation, but the nature of the crime with which he was charged is not known.

He was probably confined in the hulks in the Thames during the two years which elapsed between his conviction and the sailing of the fleet at the beginning of 1787. Amongst his fellow prisoners he was very naturally referred to as "Julius Caesar." Later on, in the records of early New South Wales, he is almost invariably styled "Black" Caesar.

One of the prettiest islands in Port Jackson has the distinction of having given us our first bushranger.

The principal and almost the only policy of the Government of New South Wales during its earliest years consisted mainly of finding something to eat for the thousand or so of people who were in its charge.

The country itself produced next to nothing in the way of provisions — nothing beyond kangaroos, bandicoots and fish — and Governor Phillip's desire to get all the available land under cultivation as soon as possible is doubtless the reason to which may be traced the first occupation of Garden Island.

![Sydney 1830 [view of Woolloomooloo Bay and Garden Island] Sydney 1830 [view of Woolloomooloo Bay and Garden Island]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhJCKQo9kNDy8jp-2H3QfkXLOruSu6FusCZyDW3ScYZQcp6sbCtoOl0Fe2IpX2Q-s5HdwZWR_8UMoGwSalXdgh24DGIxN2oLn1tgstUAxtLOmV7mT0fGsx9qbwQ3mLekMrPhi4RMz14xlbG/s640/New+Picture+%252828%2529.bmp) |

| Sydney 1830 [view of Woolloomooloo Bay and Garden Island] |

In the log-book of H.M.S. Sirius, under date of February 11, 1788, is the following entry: "Sent an officer and party of men to the Garden Island to clear it for a garden for the ship's company."

This is the first record of the existence of the island under the name it has borne ever since. There would seem to be little doubt that an advance party had already landed with a view to determining the suitability of the soil for agricultural purposes, and it is probable that the island was one of the spots earliest surveyed in the harbour by Captain Hunter, Phillip's second-in-command, when, with Lieutenant Bradley and the Master of the flagship he set out to explore Port Jackson.

He probably came back from one of his daily boat excursions to express the opinion that this island might be utilised to produce vegetables for the ship's company.

Most likely others visited the island to corroborate the opinion at first hand, before the Governor was approached for his sanction to its use in this way.

At any rate, within sixteen days of the landing in Sydney Cove, the preliminary arrangements were made and the garden actually started. Thus did the Royal Navy add another name to the map, for the Garden Island of H.M.S. Sirius retains the same title to-day, and with it will ever be linked the name of the flagship of the First Fleet.

There is no reason given in the records as to why the island was chosen for this experiment in agriculture, and it is not easy to imagine what it could have been.

Whilst the island was by nature a beauty spot in the harbour, clothed as it was in its virgin state with indigenous trees, shrubs, and flowering plants, it could never have been a fertile bit of ground.

When it is remembered that there is no natural water there, the handicap of the gardeners may be easily realised. On the other hand, it was imperative that fresh provisions should be grown, and there was little ground available for immediate use.

All the foreshores of the harbour were thickly timbered, and had to be cleared of trees before cultivation could be commenced. Implements and tools were scarce in the little colony, and so were practical farmers.

Whilst the two hummocks on the northern and southern ends of Garden Island were rocky, and fairly well clothed with trees, the saddle-back in the centre seems to have been comparatively free from growth.

It was this fact, probably, which induced the officers of the Sirius to select the island. It must be remembered, also, that few men could be spared from the ship for this work, as so many were required for other duties in the settlement.

There is no record of the success or otherwise of the flagship's garden, and only about one account of what was grown there has come down to us, at a later date, when the island had been handed over to the crew of another ship.

In 1803 a blackfellow was shot, whilst robbing the garden, and at the subsequent examination it was found that "the canoe of the deceased was full of maize, melons, etc., taken out of the above grounds."

The Fleet had brought from Rio de Janiero a large quantity of plants which it was thought might flourish in New South Wales—coffee, cocoa, bananas, oranges, lemons, guavas, tamarinds. At the Cape of Good Hope, also, many different plants were taken aboard, such as the fig, sugar-cane, quinces, apples, pears and strawberries.

When Lieutenant Phillip Gidley King founded the settlement at Norfolk Island he mentions in his diary that "We planted upwards of 1000 cabbages, and every vegetable at the plantation was in a thriving state. We had turnips, carrots, lettuces, onions, leeks, parsley, celery, five sorts of cabbages, corn salad, artichokes, and beet."

It is quite likely that most of these were available for planting in the little farm on Garden Island.

In spite of difficulties and discouragements, the amateur gardeners stuck to their job, and that they were more or less successful in their efforts is to be taken for granted, since they continued the good work even after the Sirius was lost at Norfolk Island in 1790.

When the ship sailed for the Cape to get supplies, Daniel Southwell, one of the master's mates, mentions in a letter home that they did not give up their garden.

"When we left that place we left a man to look after a kind of kitchen garden, situated in a small island in the harbour, and appropriated to the service of H.M.S. Sirius. Should this succeed and yield increase, 'twill prove of good use and worth the labour it has cost.

"But though we may, at our arrival, be longing for refreshments of this nature, for my own part, I will not be sanguine, for not only our black, but our still more barbarous neighbours, the convicts, may have despoiled or destroyed it."

This caretaker lived in a tent on the island, and his duties consisted as much in keeping off marauders as attending to the plants.

After the wreck of the Sirius there seem to have existed some doubts as to whom the island belonged, but these were settled by a "Government and General Order" of January 17, 1801, in which Governor King decreed that:

"Garden Island being appropriated as a garden for the Lady Nelson, no person is to land there but with Lieutenant Grant's permission, or the Governor's in his absence."

However, this did not altogether settle the question, for when Macquarie arrived he found it necessary to issue the following Government Public Notice and Order:

"It being deemed expedient that the island situated in the harbour of Port Jackson, and near to Farm Cove, called Garden Island, shall be comprised in and considered in future as forming a part of the Government Domain."

This order further lays it down that all the timber and produce of the island is to be regarded as wholly appropriated to the use of the Governor's domestic establishment, and specifies various penalties to which people disobeying this injunction will be liable.

There is not space here to go further into the history of this cradle of the bushranging industry in Australia, save to mention that for the last century or so its possession has been frequently in dispute between the New South Wales Government and the naval authorities.

A Privy Council decision of a few years ago laid it down that it is really the property of the State, from which it is at present held on lease by the Commonwealth Naval Forces.

But we must get back to our interesting bushranger, and his connection with the island. It is strange and singular that this picturesque little territory, so long the headquarters of Australia's first line of defence, should have been the starting place of all her bushranging records.

Although there is no evidence that Garden Island was ever put to the same use as a place of confinement as Pinchgut it would seem that a few convicts were sent there to work in the vegetable gardens planted for the benefit of the crew of H.M.S. Sirius. They laboured in irons, and some roughly constructed huts were erected for their accommodation.

Caesar was one of them, and it is curious to note that even then the White Australia sentiment was in evidence, for, on account of his color, none of his fellow convicts were willing to "hut" with him.

This gave the big Negro the direct offence, and he presently cleared out, taking with him a musket, ammunition, some provisions, and an iron pot. This Latter article was a serious loss to the little community, for cooking-pots were at a premium.

It was some time in April, 1789, that Caesar made his first escape from the island. He was re-captured in May, after having eked out an existence for two-and-a-half weeks by robbing at night the huts and tents of the little hamlet at the head of Sydney Cove.

It is most likely to Caesar that Captain David Collins, the Judge-Advocate, refers when he writes in his "New South Wales": "One of them had absconded and lived in the woods for nineteen days, existing by what he was able to procure by nocturnal thefts among the huts and stocks of individuals. His visits for this purpose were so frequent and daring, that at length it became absolutely necessary to proclaim him an outlaw, as well as to declare that no person must harbour him after such proclamation."

George Barrington, the famous pickpocket, in his book about the colony — The History of New South Wales, including Botany Bay, Port Jackson, Parramatta, Sydney, and all its Dependencies — has something to say of Caesar's escape and capture on this occasion.

"The latter end of May," he writes, "several convicts reported they had seen the body of a white man in a cove at a distance; a muster was called, but no one was found absent but a black named Caesar, who had absconded from the service of an officer, and taken with him a gun, an iron pot, and some provisions.

"In the course of a short time, however, he was caught, and as the idea of death seemed to have no effect on his mind, the Governor ordered him to be kept at work on Garden Island in fetters."

While on the island he was reputed to be the hardest worker amongst the convicts there employed, using his great strength towards getting a remission of his sentence—but one day he again took it into his head to abscond.

He stole a canoe and a supply of provisions. This time he became a bushranger in earnest, and his exploits kept the settlement in a constant simmer of excitement. One day it was the vegetable garden on Garden Island that he plundered, or the Commissariat Stores at Sydney Cove.

On the next he would be raiding the hut of some settler between Sydney and Parramatta. He seemed to be ubiquitous.

However, this period of liberty only lasted a month, and when he was again captured — in March, 1790 — he was banished to Norfolk Island, going there in H.M.S. Sirius on the occasion when she was wrecked. He seems to have been kept at the island for four or five years, for Barrington's next mention of him is in December, 1795.

|

| The Settlement on Norfolk Island, May 16th 1790 / George Raper |

"Caesar again fled to the woods," he says, "and lived by plundering the settlers by night. However, one good action he committed, which was killing a native that wounded Collins (a semi-civilised Aboriginal) who lived in the Settlement."

He was still at liberty in January, 1796.

"Caesar," writes Barrington, "who was still in the wilds, and several others, were reputed to have been seen in arms, and as some of the settlers were suspected of supplying him with ammunition, they were informed, that in case it should be proved, they would be implicated in the consequences of the robberies."

So eminent had our first bushranger become in his new profession that, on January 29, 1796, he figured as the principal subject of a "Government and General Order" issued by Governor Hunter. Here it is:—

GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL ORDER.

29th, January, 1796.

Countersign — 'Royal George.'

Parole — 'Hotham.'

The many robberies which have lately been committed render it necessary that some steps should be taken to put a stop to a practice so destructive of the happiness and comfort of the industrious. And as it is well known that a fellow known by the name of Black Caesar has absented himself some time past from his work, and has carried with him a musquet, notice is hereby given that whoever shall secure this man Black Caesar and bring him in with his arms shall receive as a reward five gallons of spirits.

The Governor thinks it further necessary to inform those settlers or people employed in shooting who may have been occasionally supplied with powder and shot, that if it shall be discovered hereafter that they have so abused the confidence placed in them as to supply these common plunderers with any part of their ammunition, steps will be taken immediately for their punishment, as they will be considered accomplices in the robberies committed by those whom they have supplied.

Captain Collins states that some attempt was made to trace the muskets issued, but that it met with little success.

A further Order of Governor Hunter's provided for the registration of arms.

"Some few settlers, who valued their arms as necessary to their defence against the natives and against thieves, hastened to the office for their certificates; but of between two and three hundred stands of arms which belonged to the Crown not fifty were accounted for."

Collins also mentions that Caesar was by way of being something of a scapegoat. Every loss of property was set against his account, and it seems quite likely that he was blamed for many robberies that he had nothing at all to do with.

Notwithstanding the reward offered for apprehending Black Caesar, he remained at large; and scarcely a morning arrived without a complaint being made to the Magistrate of a loss of property supposed to have been occasioned by him. In fact, every theft that was committed was ascribed to him or some of the vagabonds who were in the woods, the number of whom at this time amounted to six or eight."

Our first bushranger had unquestionably founded an industry!

But the end was at hand. Writing in February, 1796. Collins records the finish of this pioneer.

"On the 15th," he says, "a criminal court had met for the trial of two prisoners for a burglary, when information was received that Black Caesar had that morning been shot by one Wimbow. This man and another, allured by the reward, had been for some days in quest of him.

Finding his haunt, they concealed themselves all night at the edge of a brush, which they had perceived him enter in the dusk of the evening. In the morning he came out; when, looking round him and seeing his danger, he presented his musket; but before he could pull the trigger Wimbow fired and shot him, and he died in a few hours.

"Thus ended a man who certainly, during his life, could never have been estimated at more than one remove above the brute, and who had given more trouble than any other convict in the settlement."

In Barrington's version of the affair, he tells us that his captors took the badly wounded negro to the hut of a man named Rose, one of the settlers in the district of Liberty Plains, where he died.

Roughly, the district of Liberty Plains, originally peopled by free settlers who arrived in Sydney on the transport Bellona at the beginning of 1793, lay in the area now occupied by the Sydney suburbs of Strathfield and Homebush.

It adjoined Concord, which had mainly been allotted to noncommissioned officers of the New South Wales Corps — then very industriously earning its famous nickname of "Rum Corps."

A considerable time afterwards, the Bankstown district also had the name "Liberty Plains" bestowed upon it, but it was somewhere between the Parramatta River near Concord and the Parramatta-road that Black Caesar's doom overtook him on that summer morning in 1796.

The reward collected by Mr. Wimbow and his mate does not seem an excessive one, but in 1796 five gallons of rum meant a good deal, quite apart from its "kick and bite."

Hardly a single commodity in the settlement could be purchased without its use as a medium of exchange, and although Governor Hunter was doing everything he could to combat the rum traffic there was literally nothing else he could offer, save the promise of a free pardon to a convict, as an inducement towards the capture or killing of such an outlaw as Black Caesar.

The Governor had been compelled to admit himself that, as currency, rum had its peculiar advantages.

"Much work," he wrote in one of his despatches home, "will be done by labourers and artificers and others for a small reward in this article which money would not purchase."

It is one of the most curious facts about early Sydney that the only criminal ever gibbeted upon Pinchgut was hanged there in chains because he had killed one of his companions for the sake of obtaining half-a-bottle of rum which his victim had in his possession!

The price of bushrangers rose considerably during the ninety years of the industry's continuance as an Australian institution.

Caesar was slain for five gallons of spirits - about £2/10/- worth of rum at current prices in 1796 - Whilst the rewards offering for the apprehension of the Kellys when they met their end at Glerowan in 1880 totalled £8000.

Sources:

- Bushrangers—Noted and Notorious (1934, October 28). Truth (Sydney, NSW : 1894 - 1954), p. 19.

- `Botany Bay. Sirius & Convoy going in : Supply & Agents Division in the Bay. 21 Janry 1788' William Bradley; Courtesy: State Library of New South Wales

- Sydney 1830 [view of Woolloomooloo Bay and Garden Island]; Courtesy: State Library of New South Wales

No comments